Delhi Floods: when we harden the sponge where will the water go?

- Neural City Team

- Sep 4, 2025

- 5 min read

Every monsoon, Delhi replays a script it never seems to rewrite. In September 2025, the Yamuna surged to 207.43 metres—its third-highest level since record-keeping began. Markets went under, buses turned into boats, and more than 12,000 people were pushed into relief camps overnight.

The images are jarring, but are they surprising? Delhi’s flooding is not an act of sudden nature. It is the result of choices—some made decades ago, others repeated every day—that turned the river’s floodplain into a settlement and the city’s drains into chokepoints.

Why Does Delhi Drown?

Rain alone doesn’t drown Delhi. Geography and governance do.

When the Hathnikund barrage upstream in Haryana releases water after heavy rain, that surge barrels into Delhi within hours.

Historically, this wasn’t catastrophic. The Yamuna’s floodplains—almost 97 sq km of fertile land—soaked up excess water like a sponge. But today, those sponges are paved, encroached, or built over.

Meanwhile, the city’s drainage is a maze. Delhi has over 300 documented drains, but few are properly mapped end-to-end. Some end in blocked outfalls. Others cross-connect unpredictably with sewers. The result: rain and river water ricochet through pipes and gullies, only to bubble back onto streets and homes.

How the Floodplains Became Neighbourhoods

Why do people live where the river wants to flow?

The Yamuna’s floodplains were never meant to be real estate. A geomorphic map of

Delhi shows the river’s ancient pathways—meanders, sandy bars, and fertile patches that worked like sponges when the water swelled. For centuries, these were safety valves for the city. Then, slowly, they became neighbourhoods.

The story starts with Partition in 1947. Refugees poured into Delhi, but formal housing was scarce and costly. The floodplain land—cheap, close to work, and seemingly available—became a refuge. Temporary huts rose first, but brick walls followed.

By the 1970s and 80s, another wave of migrants—workers, farmers’ children, job seekers—found the same logic irresistible. The Khadar’s fertile soil meant vegetables could be grown, animals grazed, and water drawn with ease. For a city of limited options, the floodplain was a paradox: unsafe, but liveable.

Politics added fuel. Evicting families risked votes, while tolerating settlements brought support. Over time, services crept in—water pipes, power lines, ration cards. What was “unauthorised” began to look permanent. The result: more than 3 million Delhiites now live in colonies or villages in flood-prone zones.

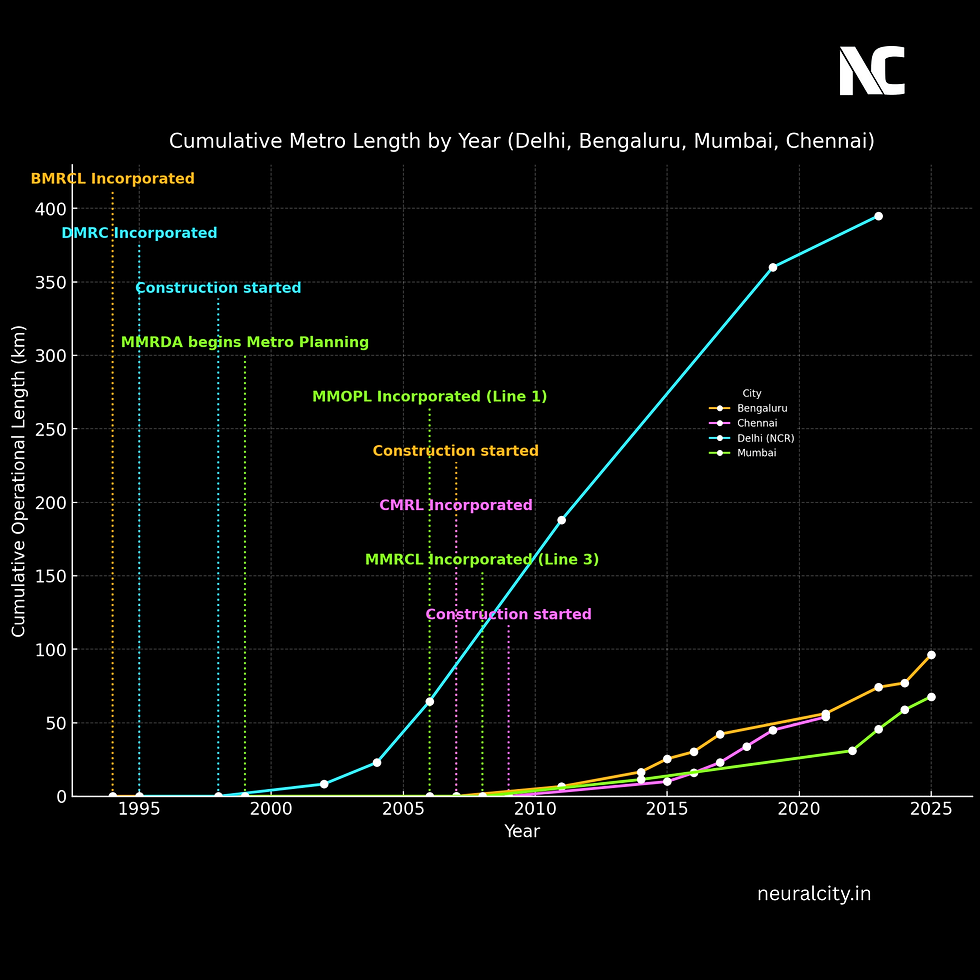

And it wasn’t just the poor. Large-scale projects—roads, metro yards, even government facilities—sliced through the floodplain, cementing the idea that if big players could build here, so could everyone else. The floodplain’s natural buffers shrank under layers of brick, concrete, and asphalt.

The question almost writes itself: when we harden a sponge, where will the water go?

The answer is visible every monsoon. What should have been Delhi’s breathing space has become its choke point.

The Situation Today

Delhi’s vulnerability is no longer hidden—it is mapped in people’s lives.

Population at risk: Nearly 3.5 million people—one in six Delhiites—live in unauthorized or low-lying settlements, many within the Yamuna flood zone.

Infrastructure mismatch: Sewage treatment plants exist, but many fail or remain underutilized. Large drains still pour untreated waste into the river.

Blind spots: No reliable, city-wide map shows where all drains lead, or how water actually flows during surges. Planners often discover blockages only after disaster strikes.

It is a system built for failure: relief over prevention, patchwork fixes over systemic visibility.

The Sponge City Idea: Are We Adopting It?

The global concept of “sponge cities”—urban landscapes that absorb, store, and reuse rainwater—sounds attractive. In China, entire districts have been re-engineered with permeable pavements, wetlands, and green roofs. In India, smaller pilots in Chennai and Indore have tried rain gardens and decentralized recharge systems.

But can this work for Delhi’s reality, where monsoon floods bring massive surges over just a few days? The answer is: only partially. Small interventions like gardens and permeable pavements help in local waterlogging—keeping colonies, markets, and roads usable during moderate rain. But they cannot by themselves buffer the billions of litres released in a Yamuna flood surge.

For that, Delhi needs land set aside to hold water at scale—urban lakes, revived wetlands, and above all, restored floodplains. The city does still have this land, mostly in the Yamuna Khadar, but it has been steadily encroached upon by settlements and construction. Without reclaiming and protecting these natural buffers, sponge city ideas risk being token gestures.

A meaningful Delhi-version of the sponge city model would therefore need two tracks:

Macro-scale buffers: floodplain restoration, urban lakes, and catchment wetlands to take the monsoon shock.

Micro-scale fixes: permeable pavements, rain gardens, and green infrastructure to manage neighbourhood-level waterlogging and recharge groundwater.

Only when both are pursued together does “sponge city” stop being a buzzword and start becoming a survival strategy for Delhi.

What Would Change the Script?

To chart a different path, both technology and administrative action must lead the way.

1. Technical Tools: The Engine of Change

Predictive AI Use rainfall forecasts, barrage release data, and historical flood patterns to issue warnings hours—even days—ahead.

Unified GIS Overlay maps of encroachment, drainage infrastructure, demographic risk, and flood zones for visual decision-making.

Citizen Platforms Launch mobile and web-based apps that enable residents to report waterlogging, view risk alerts, and access evacuation guidelines.

2. Administrative & Political Action: The Ground Truth

What’s Working

Delhi Master Plan 2041 (MPD-2041) aims to regulate floodplain land use, designate green zones, and relocate illegal colonies—offering a framework for resilience.

Delhi Development Authority (DDA) and National Green Tribunal (NGT) orders have, at times, ordered removal of encroachments and barriers, and mandated restoration of inundation zones.

Delhi Water Action Plan (Draft) includes upgrades to sewerage networks and treatment capacity, especially in vulnerable zones.

What’s Not

Implementation Gaps: Many MPD-2041 recommendations are still on paper. Funds and political will for resettling informal settlements often lag.

Electoral Politics: Evictions, even when necessary, are politically sensitive. Authorities often default to tolerance to avoid backlash—fueling settlement permanence at the cost of safety.

Jurisdictional Fragmentation: Multiple agencies—MCDs, DDA, Delhi Police, Revenue, Irrigation, NDRF—have overlapping domains. Coordination is weak, especially during crises.

Data Silos: Government departments don’t always share data. Drain maps, encroachment records, and flood histories sit in disconnected systems, slowing informed response.

This is not just Delhi’s problem. Every fast-growing city in India and South Asia faces the same pattern: risky settlement, weak mapping, and ad hoc flood response. The difference lies in whether cities choose to see what the data reveals.

Neural City’s Vision

At Neural City, we believe this is more than disaster management. It is about building a Unified GIS Platform —where every street, drain, and settlement is mapped, monitored, and connected to decision-making.

Better data leads to better governance.

Better governance leads to a better quality of life, especially for the poor, women, children, and elderly who suffer most when the city floods.

The Yamuna floods are a warning, but also an opportunity: to turn India’s cities from reactive to resilient.

To replace blind spots with intelligence. To ensure that the next surge of water meets not just resistance, but foresight.

Because when the river comes home, the question is not whether Delhi will flood—it is whether Delhi will finally learn.

Comments